The 17th of Tammuz starts the solemn “three weeks,” a period in the Jewish calendar which act as a remembrance of the worst tragedies to befall the Jewish people. The 17th of Tammuz itself recalls several historical events: the breaching the walls of Jerusalem, the ceasing of Temple sacrifices, the burning of the Sefer Torah by Apostomos, and most originally, the breaking of the original Ten Commandment tablets by Moses after the sin of the Golden Calf. It is a day of fasting and a call for teshuvah (repentance/return) as Jews are meant to reflect on what has been lost.

However, when I say, “what has been lost,” that phrase may have far heavier implications than most of us realize. Aside from Jewish unity, Solomon’s Temple, and the countless deaths that resulted from the destruction relating to these three weeks, a Midrash in Yalkut Shimoni discusses that the whole nature of the holidays of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot were changed because of the sin of the Golden Calf.

“Rabbi Levi taught: God had intended to give the Jewish People one festival in each of the summer months. In Nissan there is Pesach. In Iyar there is Pesach Sheini. In Sivan there is Shavous. As a result of their sins and evil actions, three others were taken from them. Tammuz, Av, and Elul, and Tishrei replaced them. Rosh Hashanah replaces the festival that ought to have been in Tammuz. Yom Kippur replaces the festival that ought to have been in Av. Sukkot replaces the festival that ought to have been in Elul. “Rabbi Levi taught: God had intended to give the Jewish People one festival in each of the summer months. In Nissan there is Pesach. In Iyar there is Pesach Sheini. In Sivan there is Shavous. As a result of their sins and evil actions, three others were taken from them. Tammuz, Av, and Elul, and Tishrei replaced them. Rosh Hashanah replaces the festival that ought to have been in Tammuz. Yom Kippur replaces the festival that ought to have been in Av. Sukkot replaces the festival that ought to have been in Elul.”

If we take this Midrash at face value, what does it mean that Rosh Hashanah was meant to be celebrated in Tammuz? (I hope to get to the other holidays mentioned in future blog posts.)

What the Golden Calf Cost Us

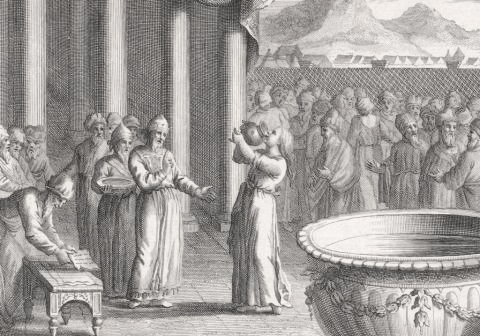

To answer that, let’s reflect on what happened on the 17th of Tammuz. 40 days earlier, the Jewish people heard God speak at Mount Sinai and Moses went up to learn the rest of the Torah. But due to a miscalculation, the Jewish people thought Moses was late in returning. They panicked and in their desperation, turned to idolatry. Moses returned from Mount Sinai holding the first set of tablets, saw the Jewish people’s sin, and shattered these tablets.

If we turn to commentary from the Oral Torah, we get a much clearer picture of important details. When Adam and Eve were first created, they weren’t like regular humans. They were on a spiritual level beyond anything imaginable. It is only once they ate from the Tree of Knowledge that they were lowered spiritually and became more associated with their physical nature (hence why they suddenly decided they needed clothing). After the Jewish people decided to accept the Torah and then heard God speak, they were restored to an exalted spiritual level, though not quite that of Adam and Eve, but the closest yet in human history. Living at such a level, you think it would be impossible for them to succumb to worshiping an idol. But when one gains power, that means more responsibility, more consequences for actions, and even greater chance for error. It can be scary. Without a proper guide (Moses), it becomes a little more understandable why they would panic and make such an error.

As for Moses, why did he shatter the tablets? I go into more depth on this concept here. But it is said that the original tablets were a revealed and open miracle. The words could be read from any angle or side, the inscription fully pierced the stone, but in the case of a letter like a mem sofit, ם the middle didn’t fall out, and when one learned from these tablets, the ideas were never forgotten. Moses realized that if Jewish people were worshiping a cow made of gold, the miracles he was holding would become an idol in and of themselves.

Had the Jewish people stayed true, when gazing upon the tablets, they would have finally become elevated to the level of holiness of Adam and Eve. But instead, they crashed back to the state of existence before Mount Sinai.

The Nature of Rosh Hashanah

The holiday that was meant to be celebrated in Tammuz wasn’t going to be the Rosh Hashanah we know today. But some element of Rosh Hashanah would have been present in this Tammuz holiday. What could that element be? When we talk about Rosh Hashanah, we know it has the following aspects. 1) It’s the anniversary of creation, aka New Years. 2) It is the day of Judgement. 3) It is the day of the sounding of the Shofar. 4) It is the Day of Remembrance. 5) It is the day we acknowledge God’s Kingship. 6) God is said to be “in the field” or more present during the Yom Noriaim (Days of Awe).

Which of these elements relate to the state of being mentioned above in the 17th of Tammuz story? The first idea, the anniversary of creation, is actually a misnomer. Rosh Hashanah is the creation of Adam, particularly when God breathes a soul (specifically the elevated soul known as the neshama) into Adam. Though clearly the 17th of Tammuz couldn’t be a calendar remembrance of that event, it does mark a return to that elevated nature. Jumping to the final two elements: God as King and God being “more present,” they’re really one in the same. The closer we are to God, the more we see His guiding hand in the world and thus more truly understand that He is King. That is all an outgrowth of a developed personal relationship with God. This is the true crux of the tragedy of the 17th of Tammuz.

At its core, the sin of the Golden Calf is understood to be an act of infidelity, quite possibly the most damaging thing a relationship can go through. If we look at the listed tragedies of the day, we can all see them as relating to a damaged relationship. One of the first acts of a Jewish wedding is when a bride circles the groom seven times, in effect creating an space of intimacy that only exists between the couple. The breaching of the walls of Jerusalem is a brutal metaphor of that intimacy and security crumbling. The cessation of the Temple sacrifices was the next listed tragedy. The Hebrew word for sacrifice is korbon, which comes from the Hebrew word, to bring close, in effect further severing the ability to become close to Hashem. The burning of the Torah scroll is as if the love letters were destroyed and intimate thoughts became forgotten.

Finally, we have the destruction of the tablets. At the very end of the Torah, the commentator Rashi praises Moses for destroying the tablets. But if we are observing a fast day because of that act, how could it be good? To understand this, we have to look to the ritual known as sotah. Without getting too technical, the idea is that if a wife is suspected of adultery and her husband forbids her from being with the man the husband is suspicious of, and the woman still secludes herself with that man, then the husband and the wife go to the priests (the kohanim). The Priests have the woman drink “bitter waters” which will prove her guilt or innocence. But in order to make these “bitter waters,” the name of Hashem is written then destroyed (which is normally forbidden) and put into the water. Now this ritual wasn’t about proving a woman is unfaithful, but instead about restoring peace and trust between the couple. And so for this shalom bayis (peace in a home) Hashem allows his name to be destroyed. It is for this same motivation of shalom that Moses destroyed the writing of Hashem. In the way a husband must learn how precious the relationship with his wife is in the face of losing her forever, the Jewish people had to face the possibility of losing their relationship with Hashem.

The 17th of Tammuz marks a period of “separation” if you will, that should have been one of tremendous closeness. That intimacy and availability is now only available during Rosh Hashanah. But perhaps if we go into the fast with that understanding in mind, we can make our teshuvah a springboard to rekindle that relationship that could have been. Surely, if that effort is made now, it could lead to a brilliant reconciliation come Rosh Hashanah.