In parshas Lech Lecha, Yitzchok, or Isaac, is foretold to be born as the 2nd forefather of the Jewish people. Yitzchok represents gevurah (restraint, discipline, devotion) yet his name means laughter. Though he would have some difficulties in his life; blindness, being deceived by his wife and son, almost being sacrificed by his father, he would always have the ability to look at life from the bigger picture and laugh. I think that’s something all of us could use more of.

But where did he get this trait of laughter from? According to Nachmanides, it may have all been due one moment from Avraham.

“ I will bless [Sarah], and she will be [a mother] of nations, kings of peoples will descend from her.’ Avraham fell on his face and laughed. He said in his heart, “Can a hundred year old man have children? Shall Sarah, who is ninety years old give birth?” (Bereishis 17: 15-17)

Elokim said: “Indeed, your wife Sarah will bear you a son and you will name him Yitzchok.” (Bereishis 17:19)

Hashem reveals to Avraham that after all his decades of waiting, he will finally have a son to carry on his legacy. Avraham’s reaction? Laughter. A deep, grateful, appreciative laughter of relief and joy. Nachmanides says that Hashem named Yitzchok because of Avraham’s expression of gratitude and faith. Remember that names in Hebrew aren’t arbitrary but reflect the essence. Avraham’s long-held prayers were finally answered and that exuberance became his son’s essence.

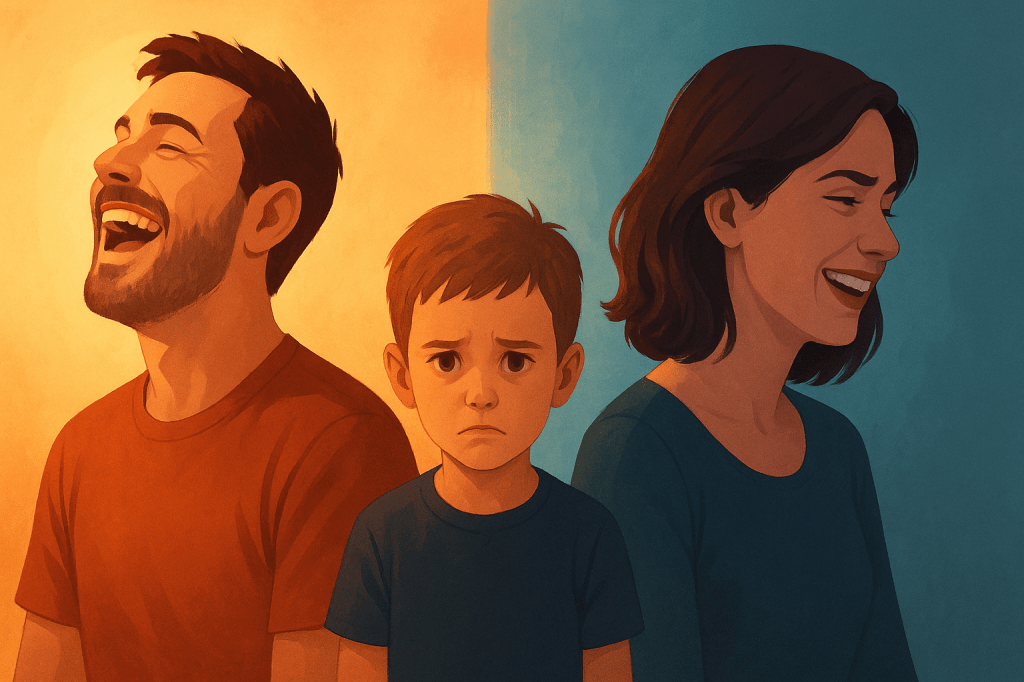

I think that there is an important lesson here about our behaviors, that the smallest and seemingly insignificant reactions can be perceived by the people around us. Especially our children.

My daughter just turned two years old. There’s one stuffed animal we call Squishy, that my wife got in Japan. Then the other day we were playing with a globe, pointing out countries and we got to Japan. Our daughter said, “Mommy got Squishy in Japan.” My wife and I couldn’t believe it. Now we may have pointed out to our daughter, but it was months ago. Certainly before ever started speaking. The things she picks up on are incredible. If she absorbs words we barely remember saying, how much more does she absorb our moods, tones, and the reactions we think we’re hiding?

Spiritually speaking, it is even more profound. Avraham hadn’t even conceived Yitzchok with Sarah yet. It would be over a year before Yitzchok would be born. But when talking to Hashem, Avraham’s reactions profoundly influenced his future reality. When Sarah hears the news of the prophecy in next week’s parsha, she will laugh as well. But her laughter has a different tone.

“Sarah laughed to herself saying, “Now that I am worn out, shall I have the pleasure [of a son] my husband being [also] an old man.” Hashem said to Avraham, “Why did Sarah laugh saying, ‘Can I really give birth when I am old?’ Is there anything too far removed from Hashem?” (Bereishis 18:12-13)

I wouldn’t go so far as to say Sarah was incredulous, but clearly there’s some sort of skepticism, and certainly not quite the joy Avraham felt. Though when Yitzchok is born, she does laugh in the way Avraham did. “Sarah said, ‘Elokim has given me laughter. All who hear will laugh with me.’” (Bereishis 21:6) But in the first instance, she did have some doubt.

If Avraham’s laughter of faith shaped Yitzchak’s joy, perhaps Sarah’s laughter of doubt shaped a hesitancy in trust. Not with regards to Hashem, but perhaps with his relationships with the women in his life.

After Sarah dies, Yitzchok marries Rivka. When she comes into Yitzchok’s tent (Bereishis 24:67) Rashi comments, “He brought her into the tent and behold she is his mother Sarah. That is, she became the image of his mother Sarah.” In a profound sense, Yitzchok’s relationship with Rivka likely paralleled his relationship with Sarah (in the way many of our spousal relationships share parallels with our parents.)

So when it came time for Yitzchok to bless his sons, Yaakov and Esav, Rivka found it necessary to deceive Yitzchok. Was this because Rivka was a deceptive woman? She did come from the house of Lavan. But I really think it was because there may have been a lack of trust between her and Yitzchok. When Sarah felt it necessary to cast Ishmael out of the home because of his influence on Yitzchok, though Avraham didn’t like it, God told him to listen to Sarah and he did. But for Yitzchok a deception was necessary. Perhaps that one moment from Sarah all those years ago implanted in Yitzchok created this very problem.

Whether my interpretation of Sarah’s laughter is correct or not, clearly everything we do is perceived by those around us on many levels. But what we learn from Avraham and Sarah is that those traits can be communicated even when we think we are “segmenting” our lives. If we behave one way with our friends at the bar, but at home we try to act more refined or elevated, the Torah seems to be telling us our other behaviors will still come through. Even if in subtle or seemingly imperceptible ways, they rub off on those around us. When it comes to our children, that internalization is exponentially greater.

Yitzchak’s laughter reminds us that our inner reactions echo far beyond the moment, sometimes even across generations. If Avraham’s joy could shape his son’s essence, so can our quiet moments of faith, gratitude, or frustration shape those who look to us. The Torah teaches that laughter isn’t just emotion; it’s legacy.