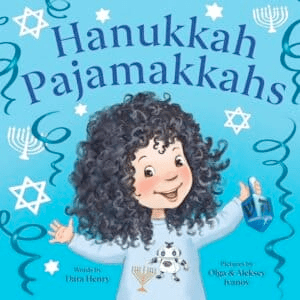

My sister wrote a charming and fantastic Chanukah children’s book. Hanukkah Pajamakkas follows a determined girl named Ruthie, who gets a set of Chanukah pajamas on the first night. But with the Chanukah pajama party on the eighth night, Ruthie’s parents suggest that she should wait to wear them so they can stay clean for the party. Ruthie insists she can not only wear her new pajamas every night of Chanukah, she will keep them spotless! And so every night, Ruthie engages in some activity which is a recipe for a laundry disaster (making latkes, decorating with glitter, etc). By the end of the holiday Ruthie’s pajamas are stained, speckled, and even a little soiled, but still SPOTLESS.

But I’m not just plugging my sister’s book for Chanukah. There’s a very interesting connection between Ruthie’s pajamas and a focus of clothes in Parshas Vayeishev.

Famously, Yaakov gives Yosef the coat of many colors. It’s so famous that Donny Osmond sang about it on Broadway. The coat inflames the jealousy of Yosef’s ten older brothers and before he knows it, Yosef is in a caravan having been sold as a slave. Rashi points to a Midrash that specifically blames the coat for Yosef’s misfortune. “There is a Midrashic statement that in the word wool (פסים) we may find an allusion to all his misfortunes: he was sold to Potiphar (פוטיפר), to the merchants (סוחרים), to the Ishmaelites (ישמעאלים), and to the Midianites (מדינים).” (Genesis Rabbah 84:8)

But Yosef’s misfortunes don’t stop at being sold to the house of Pharaoh’s chief executioner Potiphar. After a scandalous accusation by the Potiphar’s wife, Yosef is thrown in prison for 12 years. Why does the Midrash only blame Yosef’s coat for the misfortunes up to Potiphar’s house and not prison? Well interestingly enough if we look at the scene between Yosef and the wife of Potiphar the Torah says, “She grabbed him by his garment saying, ‘Be with me.’” Then within the next eight verses, the story mentions the word garment five more times! “She grabbed his garment, he left his garment, she saw he left his garment, she cried out that he left his garment, she laid his garment, ‘he left his garment’ with me.’” (Bereishis 39: 12-18) We get it. Yosef left his jacket. Why does the Torah need to emphasize it six times?

Then there’s one more mention of an article of clothing in the parsha. In the story of Yehuda and Tamar, when Tamar disguises herself, she asks for a security deposit from Yehuda in the place of her payment. She asks for his signet ring, his staff, and his cloak. Does Yehuda’s cloak have a connection to Yosef’s colorful coat, his garment, and Ruthie’s pajamas?

After Yosef is sold by the brothers, they take the coat, rip it to shreds, dip it in blood and present it to their father saying, “‘We found this. Please identify it. Is it your son’s coat or not?’” He [Yaakov] recognized it and said, ‘It is my son’s coat.’” (Bereishis 37:32-33) When Tamar is about to be burned at the stake for infidelity, she says “‘By the man to whom these belong am I pregnant’ She said. ‘Please recognize to whom this signet, cloak, and staff belong.’ Yehuda recognized them and said, ‘She is righteous, it is from me.’” (Bereishis 38:25-26) And finally with the wife of Potiphar, she identifies Yosef as her assailant because she has his garment. In all three instances the garment is used to identify the person long after they are gone.

Obviously our clothes are a profound expression of our identity. Uniforms identify us with a job or school which may limit our expression, but in the place of our individuality, we represent the institution we’re serving. Clothing can be used as a form of rebellion to go against the norms and set yourself aside from everyone else. And if you find yourself in gang territory, wearing the wrong color may mean the difference between life and death. But most of the time, the clothes we wear are just a way to be comfortable, warm, and hopefully help us feel good about how we look.

At what point are we relying on our clothes to say more about our identity than what should define us? Our thoughts, speech, and actions. Yosef’s coat of many colors was loud in the idiomatic fashion sense of the word. But metaphorically the jealousy it created was louder than any pleading Yosef could make to his brothers. Yehuda could have denied the evidence Tamar brought forward. In fact, the righteousness of Tamar is that she never exposed Yehuda to anyone else, the evidence was only presented to Yehuda. But it was upon seeing his garment that Yehuda says, “She is righteous, [it is] from me.” He realized how he had fallen short of who he was supposed to be.

But what’s so incriminating about a garment that the wife of Potiphar happens to have? If you left your shirt somewhere, who would know it was yours? But the Torah emphasizes it six times. The beginning of the parsha refers to Yosef as a “lad” despite also saying he was 17. Rashi comments that this indicates, “He did things that were childish, he fixed his hair, and touched up his eyes so that he should appear handsome.” Obviously he was concerned about his appearance and it’s safe to say his clothing factored into that.

The colorful coat resulted in him ending up at Potiphar’s house. But clearly, Yosef hadn’t learned his lesson. He was still childishly concerned about his appearance. It’s only when he has his confrontation with the wife of Potiphar that something changes. Five of the six mentions of the garment say he “left his garment.” I believe it is at this point, Yosef grew up. He realized what trouble his vanity had gotten him into. By being seduced by the wife of Pharaoh’s chief executioner, Yosef realized it was time to leave the vanity behind. So he left the garment behind too.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting some new articles to fill your wardrobe for Chanukah. And I’m not saying that clothing isn’t important or useful. Later on, the Torah will go into copious detail about the vestments of the kohanim (priests) and the Kohen Gadol. But the question to ask is does the wardrobe really help actualize who you are? Or does it communicate something you don’t want to say or have made it the primary aspect of your identity? The war of Chanukah was fought over Jewish identity. It wasn’t about the Greeks trying to kill us. It was about, would we assimilate into Greek culture or would we identify as a distinct Jewish people? Those who became Hellenized lost sight of what made being Jewish so special.

The mitzvah of the menorah is that we have to light it in a place to be seen publicly. But the origin of the dreidel was that it was a way for children to learn Torah in secret when practicing Judaism was forbidden. The message of Chanukah is that we should know what it means to be a Jew because that identity can and has come under threat. So how do we express our identity and does it reflect who we really are?

I have to commend Ruthie in my sister’s book because she refuses to let her pajamas limit her from what she wants to do. Ruthie celebrates all eight nights of Chanukah in the way she wants to. Her pajamas help her express her individuality and her identity in a healthy way. But on top of that, she’s ecstatic to celebrate every night of Chanukah. Which is a far more profound statement than anything she’s wearing. Had Yosef matured a little sooner, perhaps his colorful coat would have inspired unity, instead of jealousy.

This is dedicated to my amazing sister Dara Henry’s birthday as well as the refuah shleima of Yosef ben Feiygi.

This was superb and the book looks good!

LikeLiked by 2 people